Is AI intelligent enough to serve vulnerable communities?

Developing AI for development

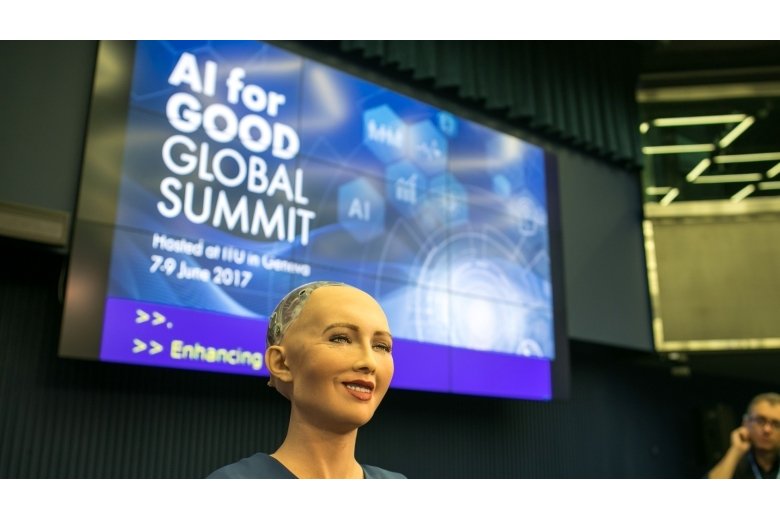

Sophia, Hanson Robotics Ltd., speaking at the AI for Good Global Summit, ITU, Geneva, Switzerland, June 7-9, 2017. © ITU/R.Farrell

By Rabi Thapa

The late 2022 launch of ChatGPT, OpenAI’s generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbot, sparked a media frenzy about the onrushing evolution of AI and what it portends for the human race and the planet at large. During the recently concluded Global Digital Summit, World Bank President Ajay Banga observed that “even people who are relatively naive about AI are rushing toward AI, because of the fear of being left behind.”

AI is not new: it is already being deployed across many sectors of development. However, its evolution from “If X, Then Y” rules-based systems to “deep” machine learning systems that mimic human neural networks has been remarkable. The discourse on the pros and cons of AI has spurred fast-tracking of regulations to govern its use, and conferences on the new technologies have proliferated.

Amidst the perception that AI is everywhere, a critical disclaimer should be made regarding the digital divide. A third of the world's population does not have internet access, and almost 800 million lack access to electricity, mostly in regions where development efforts are focused. Given the pace of AI innovation and uptake in the Global North, we are likely to see an even starker “AI divide” in countries where the fundamentals of a digital economy do not exist. So what is the lay of the land with AI in the development sector, and how does this affect vulnerable communities that may be negatively impacted by development projects?

What are we rushing toward?

There’s no question that AI is big: a 2017 report by PwC Global estimates that it could add US$15.7 trillion to the world economy by 2030. But who is this value for, and what does the AI revolution mean for Agenda 2030? In fact, AI is seen by many as critical to the fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are aligned with the World Bank Group’s twin goals of ending extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity.

At the launch of the United Nations High-Level Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence in October 2023, Secretary-General António Guterres declared that AI could “supercharge” progress on the SDGs. Research from the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden has found that AI that aids decision-making, prediction, knowledge extraction and pattern recognition, and logical reasoning could help achieve 134 out of 169 targets across the 17 SDGs. Examples of proven AI benefits include precision agriculture, medical diagnostics, teacher support and virtual tutoring, and efficient use of water and energy.

Numerous projects funded by the World Bank spotlight the benefits of AI for poor communities. For example, mapping, geospatial analysis, and machine learning helped evaluate the accessibility of social protection services in Tunisia to beneficiaries during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Pakistan, the Bank prototyped with AI and developed algorithms to improve housing finance loans management for families working in the informal sector. AI has also been used in Nigeria to boost civil works monitoring and citizen engagement through evaluation of cell phone responses using tag clouds, opinion mining, and sentiment analyzers.

Playing catch-up

The emerging AI divide is of concern. Stela Mocan, Manager of the World Bank’s Technology & Innovation Lab, which was involved in the AI projects in Pakistan and Tunisia, says, “There is a growing interest from our client countries toward leveraging AI technologies, but we have to bring clarity about whether they are ready for AI in terms of data, infrastructure, skills, digitalization levels, and on the legal and policy frameworks. Can you implement an AI project in a vacuum?”

Alongside growing anxiety about AI risks for cybersecurity, misinformation, privacy, copyright, ethics, and jobs, there is also the question of whether AI tools mostly developed in the Global North are appropriate for developing countries. AI is only as good as the data that is fed into it. Algorithms trained on news reports that contain societal biases against women and girls will reproduce these prejudices, and may inhibit the achievement of SDG 5 on gender equality; similar risks apply to all vulnerable and marginalized communities. The KTH report finds that 59 SDG targets could be inhibited by the new technologies. For example, AI-enhanced agricultural equipment may not be accessible to small farmers in developing countries, negatively impacting SDG 2 on zero hunger.

In the Philippines, Senior Environmental Engineer Maya Villaluz, who uses AI-assisted geospatial mapping for a major agribusiness program, warns against a one-size-fits-all approach: “The World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework requires site-specific assessments and environmental and social screenings to be carried out for each subproject activity; this creates demand for analysis that can be aided by AI. But to be able to identify the actual needs of people in a developing country you need to understand the diversity of their ecosystems. If no research has been done, and there is a lack of baseline data, it is important to apply professional judgment in order to verify and validate useful data from a universe of random and unrelated information.”

AI for accountability mechanisms: what is the potential?

How might AI assist independent accountability mechanisms (IAMs) in reaching communities? Esteban Tovar Cornejo, Social and Environmental Specialist at the Independent Consultation and Investigation Mechanism (MICI) at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), explains how the IDB has embraced AI by partnering with Microsoft to optimize the use of its coding chatbot, Co-Pilot. An early task was the time-saving use of AI to generate Terms of Reference across four languages for new hires. Cornejo and his team are also experimenting with prompts for AI that will help MICI make case presentations to stakeholders: “We can ask the AI tool to imagine that it is a project team leader within the IDB who has received a complaint. What information is then going to be useful for that team leader? We can assign different roles across sectors so we can better understand how to work with IDB management, civil society, or indigenous people.” In the future, external stakeholders may be able to use AI to ask the same questions to be better informed about cases, potentially through a dedicated MICI phone app.

The challenge lies in asking the right questions, and drawing on the right data. This is where the IDB’s progressive approach toward AI, which builds on its work on big data, provides a launching pad for MICI. But the need to ensure consistently high-quality data means that the MICI team remains primarily focused on internal innovation and efficiency. Several other IAMs contacted by Accountability Matters indicated that while exploratory AI work is ongoing, it was premature to share findings.

Natural language processing models may offer a range of options for IAMs. Companies have long been employing automated chatbots for complaints handling on a large scale. Automation may be limited to acknowledging and filing complaints, but AI can search for key tags and analyze the emotional content of complaints. It could then decide on whether a given complaint should be escalated to a human interlocuter. For IAMs that receive complex complaints on project impacts from community members, using AI in this way is fraught with risk, and may not even be necessary given the relatively low number of complaints received. But conversational, AI-assisted chatbots could support IAM outreach by guiding complainants to the relevant sections of websites, be it to register a complaint or to learn about specific cases.

The summarizing capabilities of AI are also improving rapidly, with recent research suggesting that human evaluators preferred AI summaries to human summaries by more than 50 percent. Coupled with instantaneous, AI-generated multilingual translations, and visualizations that simplify complex data for laypersons, summaries could help community members access content in technical documents produced by IAMs. In turn, IAMs could use AI to summarize notes and audio recordings from field visits. These could be significant time and labor-saving devices that promote transparency and accessibility. Nonetheless, caution is advised in the use of technologies developed in the Global North, as they may struggle to grasp the complexity of social dynamics that tend to characterize cases.

Megumi Tsutsui, Senior Research Associate at Accountability Counsel, acknowledges the data-related challenges involved in using AI to identify Environment, Social and Governance risks and concerns, as the International Finance Corporation’s machine-learning analyst MALENA has begun to do. Nonetheless, she hopes that AI will “lead to time savings, cost savings, and an efficiency that opens up more space to do more serious due diligence and get more input from people on the ground who are most impacted by these big projects.”

An important part of this added due diligence is ensuring that the data being used is trustworthy, and that community concerns are not being glossed over. “The people who are being affected by a lot of these projects are not generating data that an AI model would be capturing,” Tsutsui points out. “So we have to make sure that we are verifying input from communities. Their voices have to be included in some way.”

The analytical powers of AI may yet come into their own across larger, higher-level datasets. Like the IAMs whose work Accountability Counsel tracks in communities across the world, Tsutsui explains that they are approaching AI with justifiable caution. However, the use of AI is already foreseen for Accountability Console, the database of close to 1,800 complaints that Accountability Counsel manages, and the policy benchmarking exercise that underpins flagship reports on IAM policies such as the Good Policy Paper. “Comparison and benchmarking are very manual processes,” Tsutsui says. “We’re hoping that with AI, we’ll be able to do this much faster. And then we can focus on pulling out more analysis.”

A blog from the World Bank Digital Development Global Practice breaks down decision-making into “predicting outcomes and deciding what actions to take”. A defining feature of AI is that it decouples prediction from judgment. Ultimately, we retain the power to make human judgments. If AI gets better at prediction, then humans are empowered to get better at judgment. As Alexandra Todericiu, IT Officer with the Technology & Innovation Lab, notes, “Everyone is afraid that AI will replace us. But the conversation should actually be about how AI can help us be more efficient.”

Balancing hopes and fears through governance

Since 2018, the World Bank Group has initiated about 45 AI-linked projects, including innovations like MALENA and Mai, the World Bank’s AI-powered, secure chatbot. An AI governance framework is under consideration. Many international institutions and governments have drafted AI regulations, including the US, China, the United Nations, and the European Union. While their overall objectives are similar, in that they aim to ensure responsible AI that meets ethical standards, respects human rights, and reduces risks and harms, approaches vary widely across “soft” guidelines, “hard” law, and “self-regulation” that places the onus on the AI industry.

Not everyone is convinced we are doing enough. Michael Møller, a member of the Board of Directors of the Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator (GESDA) and a former Under-Secretary-General of the UN, says: “Almost everyone is running after a horse that has already bolted. We are looking at AI as we know it today, which is child’s play compared to what’s coming toward us at warp speed. We are not spending enough thought and action on the technologies of tomorrow: governance, ethics, equity issues, accountability, transparency, etc. need to be injected into AI technologies before they leave the laboratories and the universities. There’s a lot of catch up happening right now in terms of guidelines on how to govern AI. The problem is that nobody’s connecting the dots and nobody’s really speaking to each other. What we really need is a flexible, global set of rules that everybody can agree on.”

In a February 2024 visit to California’s Silicon Valley, Volker Türk, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, echoed Møller’s advocacy of “supervised innovation” for AI. Critiquing developers for lacking a “global view of the world”, Türk called on the tech industry to adhere to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: “We need responsible business conduct. We need accountability for harms. We need access to remedy for victims of such harms. But above all, to mitigate these harms from occurring in the first place, we need sound governance of AI, anchored firmly in human rights.”

It may be that we simply need to talk to each other more. Møller explains how GESDA facilitates exchanges: “We take scientists and put them together with non-scientists so that these two groups who never really spoke to each other much before can understand each other better. It’s not just one conversation: it’s a way of creating task forces that are shared by scientists and non-scientists. And these conversations have had an impact on many top scientists, who have suddenly woken up to the fact that they need to incorporate an understanding of the potential impact on society of the stuff they’re working on.”

The challenge for applying AI in development responsibly is aptly summed up by Khuram Farooq, Senior Governance Specialist at the World Bank: “People often come up with the technology, and then try and fit the tool to real-world problems. But you should never start with the technology. If somebody wants a driving license, they don’t care if it is AI-assisted or just a piece of paper—they want the permit delivered in a short period of time. Just start with the problem, then consider if AI can help.” As we approach the UN’s AI for Good Global Summit in May, the tagline of “Connecting AI Innovators with problem owners to solve global challenges” has never seemed more relevant.